A list of recently extinct animals, with pictures and facts. Discover why, and when, species have become extinct in recent times...

Extinction

Extinction is a natural process. Since the very beginning of life on Earth, species have regularly been appearing and becoming extinct. Species have an average lifespan of around 5 million years, and the normal background extinction rate sees between 10 and 20% of all species become extinct every million years.

There are several periods in Earth’s history during which the normal extinction rate has increased dramatically over a relatively short space of time. These periods are known as “mass extinctions”, and as far as we can tell, five of these mass extinction events have occurred throughout Earth's history.

The best-known mass extinction event is the Cretaceous Paleocene Extinction Event, in which all non-avian dinosaurs became extinct (along with many other animals and plants).

- You can find out more about the Cretaceous-Paleogene Extinction Event on this page: When Did Dinosaurs Go Extinct?

There is evidence to suggest that Earth is currently undergoing a sixth mass extinction event – one being caused by human behavior. Whether or not this is true, there can be little doubt that many of the animals in the list below became extinct as a result of either over-hunting or habitat loss.

You can see a list of animals that went extinct in 2023 on this page: Animals That Went Extinct In 2023

List Of Recently Extinct Animals

(Note that in most cases, the year of extinction is either estimated, or based on the last reported sighting.)

Passenger Pigeon

- Scientific name: Ectopistes migratorius

- Became extinct in 1914

In the 1890s, there were so many passenger pigeons in North America that a single flock could take more than 12 hours to pass. The species’ population may have been well into the billions, which would have made it the world’s most numerous bird species.

By 1914, the passenger pigeon was gone: the last known individual died in captivity. She was around 30 years old when she died, meaning her species went from billions to zero in the course of a single bird’s lifetime.

Like so many other animals, the passenger pigeon fell victim to the combined pressure of hunting and habitat loss. Passenger pigeons made an easy meal for anyone with a shotgun – and no laws governed how many animals a single hunter could take.

In the early 20th century, the science of ecology was in its infancy, and most people thought the natural world was immune to the effects of human activity. No matter how much they hunted, they thought the pigeons would remain.

It wasn’t only the over-hunting that led to the extinction of the passenger pigeon; the species’ natural habitat – oak forest – was at the same time being cut down. The passenger pigeon may even have survived the hunting if it weren’t for this additional threat.

Pinta Island Tortoise

- Scientific name: Chelonoidis abingdonii

- Became extinct in 2012

There are 15 or so species of Galápagos tortoise. They’re huge, long-lived reptiles famous for their role in inspiring Charles Darwin’s theory of natural selection. Among many other observations he made during his visit to the Galápagos, Darwin noticed a difference between the tortoise species on different islands.

On the larger Galápagos islands, the tortoises have shells with a low dome and a small opening for the head.

On the smaller islands, like Pinta, the tortoises evolved a very different shell shape.

The smaller islands have less vegetation, so the tortoises can’t rely on grass like their cousins on the larger islands; instead, they have to reach up to eat prickly pears and other higher-growing foods. This is why the Pinta Island tortoise had a long neck and a high opening at the front of the shell to support its unusual feeding habits.

For a short time in the early 2010s, the most famous tortoise in the world was a 100-year-old Pinta Island tortoise named Lonesome George. George was the last of his species. He had been found in 1971, when the species was already believed to have been extinct.

Scientists attempted to breed him with females of closely related tortoise species, but the experiments were unsuccessful. George died in 2012, and as far as we know he was the last of his kind.

Thylacine

- Scientific name: Thylacinus cynocephalus

- Became extinct in 1936

One of the best-known recently extinct animals is the thylacine, a species once found both on mainland Australia and on the Australian island Tasmania.

At first – or even second – glance, you might think that the thylacine was a wolf, or at least a member of the dog family, Canidae.

In fact, despite its wolf-like appearance, the thylacine was actually a marsupial – a relative of wombats and kangaroos. Like all marsupials, the thylacine’s young developed in a pocket-like “pouch” in the mother’s body.

Due to its wolf-like appearance, the thylacine was also known as the “Tasmanian wolf”. Another popular name for the thylacine was the “Tasmanian tiger”, on behalf of the stripes on its back.

The similarity between the thylacine and the wolf is explained by the theory of convergent evolution. This is the process by which unrelated animals develop similar characteristics due to having a similar lifestyle. (Another example of convergent evolution is hawks and falcons: both have sharp, tearing beaks and pronounced talons, yet belong to entirely different avian orders.)

The thylacine became extinct on mainland Australia around 2,000 years ago, probably as a result of indigenous human activity and the arrival of the dingo.

Although extinct on the mainland, the thylacine was still present on Tasmania when the first Europeans arrived. Believing it to be a threat to livestock, the Tasmanian government offered a bounty to anyone who killed one of the animals. The dogs that accompanied the new wave of settlers may also have out-competed the native thylacines for prey.

Thylacines were never very numerous (apex predators nearly always live at low densities), and their population couldn’t withstand the renewed persecution. The last known thylacine died in Hobart Zoo in 1936.

Gastric-Brooding Frogs

- Scientific name: Rheobatrachus silus and Rheobatrachus vitellinus

- Became extinct in 1985

Amphibians are currently one of the groups of animals most at risk of extinction. Hundreds of frog and salamander species are threatened by Chytridiomycosis, a disease spread by the fungi Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis and Batrachochytrium salamandrivorans.

Given time, amphibian populations might evolve resistance to the fungi, but in the age of globalization it hops around the world at airline speeds – much too fast for evolution to keep up.

Of all the species lost to Chytridiomycosis, two of the most unusual are the northern and southern gastric-brooding frogs (Rheobatrachus silus and Rheobatrachus vitellinus).

Female gastric-brooding frogs swallowed their own eggs, which then developed in the safety of their mother’s digestive tract.

The tadpoles would secrete a special chemical to neutralize the mother’s stomach acid, giving them a protected place to develop and grow (and also preventing mom from eating until the tadpoles were grown up).

Gastric-brooding frogs very nearly died out before we ever learned of their unique reproductive habits. The southern species was discovered in 1972, and their northern cousins (R. vitellinus) discovered in 1984. By 1985, both species were believed extinct.

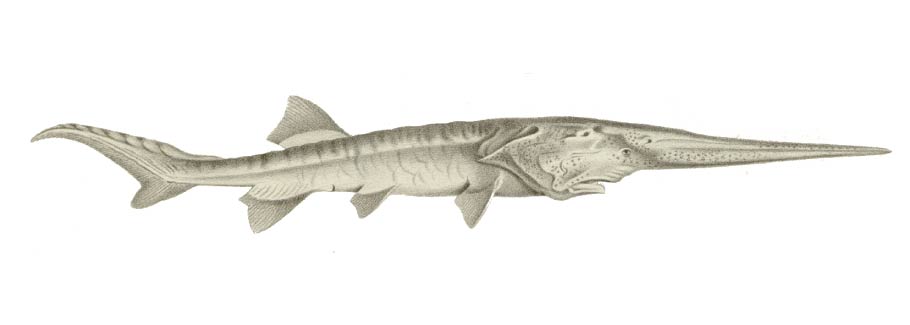

Chinese Paddlefish

- Scientific name: Psephurus gladius

- Declared extinct in 2022

The Chinese paddlefish was a huge, bizarre-looking fish that swam in the Yellow and Yangtze rivers in China.

At nearly 10 feet long, it was one of the world’s largest freshwater fish. Much of that length came from an enormous snout, or rostrum, with which the fish would probe around for prey. The Latin name gladius, meaning “sword,” is a reference to the paddlefish’s long rostrum.

By the time the last Chinese paddlefish was seen alive in 2003, the species had already been in decline for a number of years.

Both the Yellow and Yangtze rivers pass through eastern China, one of the most densely populated places on the planet. As the Chinese population grew, the paddlefish came under increasingly severe pressure from fishermen. Still, there were enough of them in the 1970s that 25 tons could be taken from the rivers every year.

As with the passenger pigeon, the Chinese paddlefish fell to a one-two-punch: first, excessive exploitation for food weakened the populations; then habitat loss finished them off.

Starting in the 1980s, dams were constructed across the rivers. These dams were built without any consideration of the local ecology, and their effect was catastrophic for migratory species like the paddlefish. Once they were cut off from their spawning pools upstream, the population rapidly collapsed.

Schomburgk’s Deer

- Scientific name: Rucervus schomburgki

- Became extinct in 1938

Thailand once had extensive grasslands and marshes around its rivers, but nearly all of this land was converted to commercial rice paddies during the 19th century.

One notable victim of this transformation was Schomburgk’s deer, an unusually large and heavily-antlered species native to central Thailand. Because of its large antlers, the species was also targeted by hunters. The antlers were prized both as trophies and for their medicinal properties. Once again, habitat loss and over-hunting worked together to wipe out the species.

Schomburgk’s deer was last seen in the wild in 1932, and the last captive individual died in 1938.

Caribbean Monk Seal

- Scientific name: Neomonachus tropicalis

- Became extinct in 1952

Caribbean monk seals were common in the Caribbean Sea until they became a target of hunters in the 18th century. The seals had few predators on land, and were therefore defenseless against armed settlers who wanted the oil from their blubber.

Like whales, Caribbean monk seals were targeted not for meat but for fuel; their blubber oil was used in lamps. Because the seals were highly gregarious, congregating in groups of dozens or hundreds on Caribbean beaches, commercial hunters could kill huge numbers of seals in a very short time.

The last known sighting of a Caribbean monk seal was in 1952.

Western Black Rhinoceros

(No image available)

- Scientific name: Diceros bicornis longipes

- Declared extinct in 2011

The rhinoceros isn’t extinct – not yet. But one major subspecies of black rhino went extinct in 2011, possibly foreshadowing the fate of these iconic African mammals.

There are two species of rhino in Africa: the white rhino (Ceratotherium simum) and the far rarer black rhino (Diceros bicornis). They’re the remnants of an ancient and diverse lineage whose members once grazed all over the world and included oddballs like the North American Teleoceros and the massive single-horned Elasmotherium. Today, the rhinoceros family has dwindled down to a handful of species in Africa and Asia.

Rhinoceros numbers have declined sharply since the 1970s, due mainly to poaching. In the years between 1970 and 1992, around 96% of the world’s black rhinos disappeared, largely due to poaching.

Poachers target rhinos because of the supposed medicinal value of rhino horn in Chinese traditional medicine (there’s no evidence to suggest that rhino horn has any medicinal properties), and because rhino horn still has value as a status symbol in some Chinese and Middle Eastern cultures.

- You can find out more about the black rhinoceros on this page: Black Rhinoceros Facts

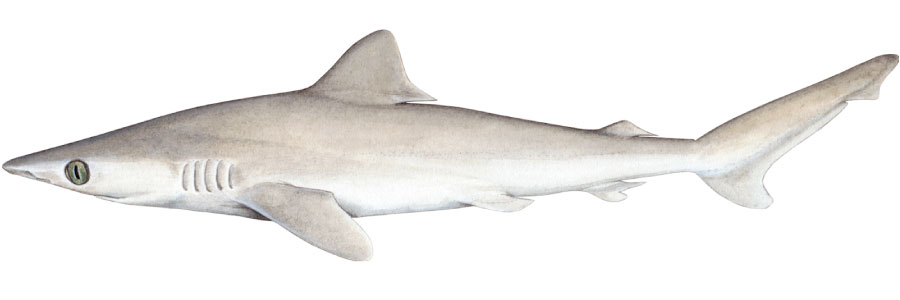

Lost Shark

- Scientific name: Carcharhinus obsolerus

- Declared Critically Endangered (probably extinct) in 2020.

Normally, if a species goes extinct before it’s discovered, we remain unaware of its existence. But in 2019, a group of scientists had the unusual experience of describing a previously unknown species of shark that is almost certainly extinct. They discovered the specimen in a museum collection, where it had been preserved for almost a century.

The new species – named the “lost shark” – had been collected and preserved at some time during the early 20th century, but all the specimens were wrongly identified as Carcharhinus porosus, a related species. Using careful measurements from the museum specimens, researchers demonstrated that these three specimens belonged to a separate species; one previously unknown to science.

The lost shark is a relative of the reef sharks, and like them it inhabited shallow, tropical waters. These are some of the most intensely overfished waters in the world, since they are easily accessible and have abundant fish.

Chiriqui Harlequin Frog

- Scientific name: Atelopus chiriquiensis

- Became extinct in 1996

The Chiriqui harlequin frog is an extinct member of the “true toad” family, Bufonidae. (There is no strict zoological difference between a frog and a toad; species with warty, dry skin are generally called “toads”.) The species lived in streams in the mountains of Costa Rica and Panama.

Male Chiriqui harlequin frogs were territorial, calling to attract females to a breeding site that they would defend from other males. The species was active during the day.

Once a common species, the Chiriqui harlequin frog was last seen in 1996, and is now considered extinct.

The Chiriqui harlequin frog, like the gastric-brooding frogs of Australia, was a victim of Chytridiomycosis. The extinction of these species demonstrates that the threat to amphibians from the disease is worldwide.

Pachnodus Velutinus

(No photo available)

- Scientific name: Pachnodus velutinus

- Became extinct in 1994

Pachnodus Velutinus was a species of snail found in the Seychelles, an island country in the Indian Ocean. It lived in high altitude forests with high humidity.

Pachnodus Velutinus became extinct after hybridizing with Pachnodus niger, another snail found in the region. Eventually there were no non-hybrid Pachnodus Velutinus individuals remaining.

Nevis Rice Rat

(No photo available)

- Scientific name: Pennatomys nivalis

- Became extinct: c. 1200

The Nevis rice rat is an extinct species of rodent that inhabited some of the Lesser Antilles Islands in the Caribbean, including Nevis, after which it was names.

The species was never identified when living, and is known only from skeletal remains found on three islands. It belongs to a group of rodents known as Oryzomyini, or “rice rats”.

Also in this group is the Jamaican rice rat (Oryzomys antillarum), another extinct rodent of the Caribbean.

Large Sloth Lemur

- Scientific name: Palaeopropithecus ingens

- Became extinct: between 1,000 and 500 years ago.

The large sloth lemur is one of three lemurs of genus Palaeopropithecus. All three species are extinct and known only from fossils. It is thought that they may have survived until around 500 years ago.

The sloth lemurs were found on Madagascar (lemurs are endemic to Madagascar, meaning that they are found nowhere else on Earth).

From the structure of their bones, the sloth lemurs are believed to have spent much of their time hanging upside-down, sloth-style, in trees. This behavior is how the species got their name; they are not related to the sloths of South America.

Climate change and human hunting led to the extinction of the sloth lemurs. The lemurs were hunted by the earliest human inhabitants of Madagascar, and due to their slow reproductive rate, were hunted faster than they could reproduce.

Golden Toad

- Scientific name: Incilius periglenes

- Became extinct in 1989

The golden toad, like the Chiriqui harlequin frog, was a member of the “true toad” family, Bufonidae. It lived in elfin cloud forest – a mountain forest habitat characterized by small trees – in Costa Rica. The species was named after the bright golden color of its skin. It bred in pools that appeared as the rainy season began.

The golden toad was categorized as being Endangered in 1986. The species’ rating was revised to Critically Endangered in 1996, and in 2004 the golden toad was formally categorized as being extinct. The species had not been seen since 1989.

Several reasons have been given for the golden toad’s extinction. These include El Niño (a local weather cycle) causing particularly low rainfall and high temperatures, and the spread of the disease chytridiomycosis, which has caused the populations of many amphibians to decline.

Utah Lake Sculpin

(No image available)

- Scientific name: Cottus echinatus

- Became extinct in 1928

Sculpins are small, bottom-dwelling fish with spined pectoral (side) fins with which they grip onto the lake or sea bed. Sculpins are found in both freshwater and marine environments.

The Utah Lake sculpin was found only in the Utah Lake, in central Utah, USA. The last recorded specimen was caught in 1928.

The species is thought to have become extinct after drought caused water levels to become low, and a subsequent cold winter caused the lake to freeze. Pollution may also have played a part in the species’ extinction.

Guam flying fox

- Scientific name: Pteropus tokudae

- Became extinct in 1967/8

(No image available)

The Guam flying fox inhabited the forests of Guam, a US-owned island in the Pacific Ocean. The species was first discovered in 1931, and the last recorded specimen was seen in 1967 (in 1968 an individual was shot). Hunting by humans may have led to the species’ extinction; another potential cause being the introduction of the Brown tree snake to the island.

Bennett’s Seaweed

(No image available)

- Scientific name: Vanvoorstia bennettiana

- Became extinct in 1886

It's not just animals that go extinct; any living species, including plants, can disappear if the conditions they require to live and reproduce are removed.

Bennett’s seaweed was a small red alga found only in two sites in Sydney Harbour, Australia.

Like many of the the animals on this list, the seaweed became extinct as a result of the destruction of its natural habitat by humans.

As the harbor was transformed by industrialization, it became increasingly inhospitable to wildlife.

Once-rocky areas of the sea bed became covered in a thick layer silt, and other areas were frequently dredged. Few seaweeds were able to survive under these new conditions, and Bennett’s seaweed became extinct at some point at the end of the 19th Century.

Many beautiful. Animals lost! So bad 😞😔heartbreaking💔.

Yeah. But look on the bright side we still some pretty amazing animals. 🐰

Heartbreaking. So many beautiful animals lost. 🙁